Morals Without a Master (Anticynical #20)

When your board members are ghosts named Kant, Machiavelli, and Camus.

Hi friends!

I have a big life update which forms the backdrop of this essay: I’ve finally quit my job at Apple to launch my own startup! This has been a long time coming and I love that I’ve finally made the jump.

Let’s just get into it.

Morals Without a Master

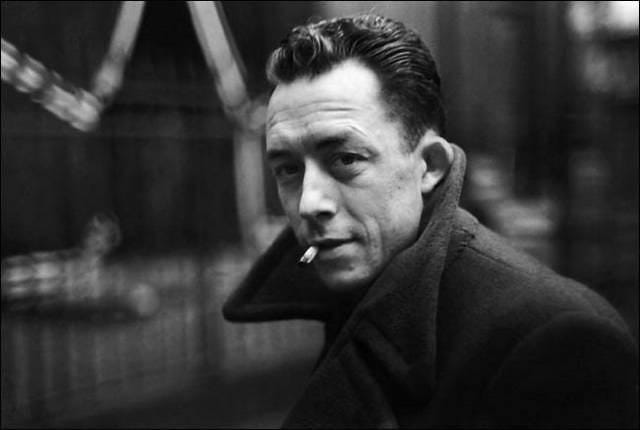

I’m at the dinner table, sitting with Immanuel Kant, Niccolò Machiavelli, and Albert Camus. The vibe of the dining room is uniquely San Franciscan: part Victorian, part modern, with chandeliers, candlesticks, and sleek black quartz finishes with LED light panels. It’s dim but not quite dark—mirroring the city’s fog-covered aesthetic.

Me: ”Gentlemen, here is tonight’s menu. We have three unsigned customers. An investor call is in 48 hours. If I write ‘three active pilots’ on the slide, I probably close the seed round. If I write ‘three pending pilots’, I probably don’t. What do I do?”

Kant straightens his powder wig, voice clipped. “A slide is a speech act. If you knowingly misstate, you will it as acceptable for every founder. Investor trust collapses. Say ‘pending’. Anything else is a lie.”

Machiavelli flicks a crumb off his sleeve. “Seed funding is not about truth. It’s about narrative control. You’re not lying—you’re casting a spell. Say ‘active.’ Then make it true. The lie becomes retroactive truth if you move fast enough.”

Camus lights a cigarette he didn’t have a second ago. He smiles, not with humor, but with recognition. “They offer you rules for a game that has none. One sells purity, the other victory. Both are phantoms to shield you from the truth: nobody is coming to tell you what to do. The universe doesn't record the choice, only that a choice was made. The rest is just the story you tell yourself afterwards. So, which lie will you choose? The lie of purity, the lie of victory, or the lie that it doesn't matter? The only truth is in the choosing.”

Me: I swirl my glass. My runway is a countdown clock in my head. My conscience is a high-frequency buzz in my ears. My desire for this to mean something is a dull ache in my chest. I stare at the empty slide on my laptop screen, the title "Our Traction" stares back, mockingly. The cursor blinks. Blink. Blink.

The investor call is in two days, but this dinner is timeless. The guests are ghosts I've been entertaining for years, the personification of a lifelong war. Their arguments are the soundtrack to every meaningful decision I've ever had to make.

There's the unyielding, demanding Morality, a voice that sounds suspiciously like my lovingly disciplinarian grandmother's, but armed with the unsparing logic of Kant. There is the seductive, pragmatic whisper of Effectiveness, a Machiavellian urge to win at all costs. And then there is the hollow laugh from the corner, from the shadows of Meaning, where Camus reminds me that the universe doesn't care about my slide deck or my soul.

This essay is an attempt to map that battlefield. It is a dispatch from the war between the person I ought to be, the person I must be to succeed, and the nagging fear that neither of them truly matter.

0. Prologue

My mom and my grandmother are some of the most idealistic and righteous people I know. Through nature and nurture, their principles are deeply embedded in me:

Never lie. Respect everyone.

Be kind to everyone.

Hard work speaks for itself.

I accepted these as the basic terms and conditions of being a decent person.

My grandmother, a school principal and disciplinarian, never yelled or threatened; she simply expected, and I behaved. Math problems after school, classical music lessons, and unwavering moral expectations were the texture of daily life. My mother, while gentler in approach, carried the same ethical gravity. She had clear ideals and values she wanted to instill in me. She didn’t want me to just follow rules—she wanted me to believe in them.

Ideals of righteousness coursed through the marrow of my bones. I thought Superman was cooler than Batman precisely because, and not in spite of, him being a goody-two shoes. Hell, I even avoided killing innocent civilians when I played Grand Theft Auto.

For both my grandma and mom, the foundation of goodness was obvious: we must be good because God. But God was dying in me long before I declared apostasy. I looked on evil—war, strife, the suffering of innocent children—and I questioned divine benevolence. Scientific theories like the Big Bang and evolution by natural selection made God’s creation powers seem redundant. But the most lethal cut was the fact of human myth-making. It is the understanding that humans have always had a proclivity for creating fantastic stories to explain their environment—and that divinity is one of the most common literary devices. This made it obvious to me that God, of the myths and stories, was a human invention, not a Truth about the universe.

By seventeen, God was irrefutably dead. And without God, I did not have a good justification for why I had to be good. But since goodness was conditioned into me, I still felt guilty when I couldn’t abide by it. Almost imperceptibly at first, but then completely, my foundation for being good became guilt—and shame.

“I feel guilty about everything, all the time,” I said to Julie, my first date since moving to the US. It was pleasantly warm in San Diego and we were at a cute ice-cream shop. I was 22. She blinked and nodded, “Why do you feel that way?” “I… don’t really know,”

I felt a gut punch, and a tightening in my chest, every time I was even a minute late to a meeting. If I’m late, I don’t respect them or their time, so I must be a horrible person. Even for something that trivial, I’d feel ashamed hours later. Maybe if I had God, I might have asked Him for forgiveness and offloaded some of my burdens. But I just had raw guilt. I felt guilty about everything I did not do flawlessly and felt constant shame about being a person who was so flawed.

This unmoored guilt became intolerable; I needed an anchor, and in the absence of God, I began searching for a system—any system—built on a foundation that couldn't die.

1. Morality

“Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”

- Immanuel Kant, Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals

In the midst of my rudderless guilt, I found Kant and his categorical imperative.

It was like discovering a law of physics for the soul. The campers’ rule—leave it better than you found it—is a great example. If you could will your personal rule as a universal rule for everyone without creating a contradiction, it was moral. If you couldn't, it was not.

But as I looked deeper, I realized this was only the entry point. The universal law was the litmus test for a deeper, underlying principle. It is captured in Kant's second, more profound formulation of the categorical imperative: to treat all of humanity, in yourself and others, never merely as a means to an end, but always as an end in itself.

This was the revelation. The Universal Law was the cathedral's architecture, magnificent and logical. But the Humanity Principle was what it was all built for—the sacred altar of human dignity. Lying wasn't just logically inconsistent, it was an act of violence against another person's rational soul. It was using them as a tool. I now had a system that was not only rational but also deeply humane. I clung to it like a man overboard clings to a spar.

It wasn’t just an armchair philosophy for me. I strove to live it and build with it. Almost like a rite of passage, one of my previous startup ideas many months (feels like years) ago, was an AI-powered dating app. I know. The premise seemed simple enough: the AI would help users improve their profiles and conversations. Applying the categorical imperative, helping someone take better profile pictures felt like a universal good—it would create a better, higher-quality dating pool for everyone. But what about coaching a user on what to say? Is providing the "perfect line" an act of helpfulness, or is it a deception? Would I be willing a world where all romantic connection is built on a script? This was a “real-world” product design dilemma, and Kant's logic was paralyzing.

And the paralysis was a revelation. That dating app question wasn’t a unique edge case, it was the template for a thousand daily choices. To will a world where all romantic connection is scripted felt monstrous. Yet to deny users a tool that might ease their crippling social anxiety felt like a violation of a different, more human imperative. The system offered no answers, only a perfect, elegant, and totally unworkable dead end. It was a philosophy for angels, not for founders.

Kant’s beautiful, rigid cathedral of reason had no room for human messiness. It offered no absolution. In fact, it was a harsher master than the God I’d abandoned. Viewed through Kant’s unforgiving lens, even a reflexive white lie was to will a world where truth has no meaning. The guilt I felt before was a murky fog; this new guilt was a blade, sharp and precise. I hadn’t escaped my prison—I had merely rationalized its walls and handed the key to a colder warden.

I had to create an updated system to survive. I called it my "relaxed categorical imperative"—an attempt to build a little chapel of human exceptions onto the side of Kant’s grand cathedral. This was a place where kindness could override truth, where context could finally matter. It was a system that permitted the lie to save a life, or the assurance to an anxious relative that "everything will be fine." It was an appeal to my own judgment, honed over a lifetime, to make appropriate compromises. But each compromise, each exception, chipped away at the foundation. The clear lines of reason blurred into the murky grey of self-justification. It wasn’t enough.

Kant had given me a ruler to measure my own soul, and the act of measurement itself became a new and constant source of torment. I had a moral system, yes, but it was a system that stood in the way of a life that worked. The voice of "Ought" was clear and loud, but I began to hear a new whisper: "Win."

2. Effectiveness

“Where the willingness is great, the difficulties cannot be great.”

- Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince

Something I thought I’d never do is play calculated bluffs to get ahead. For example, we’ve told investors we had a few letters of intent (LOIs) when some of them were signed by supportive friends at other startups. Was this really a problem? They were still legitimate LOIs signed by legitimate startups. We’ve presented a case study that was hypothetical to help customers visualize our product's potential. We never claimed that the customer was real. This was fine, right? The boy who loved Superman would have been appalled at this refraction of the truth. He would see only the lie.

But the current me understands the bootstrap paradox: you must project the reality you wish to create to get the resources to create it. I deploy these hacks while still being grounded in principles. Even though I showed a hypothetical case study, I’m honest about it being hypothetical, in the details and if asked. Similarly, I’m honest about the letters being signed by friends, when asked. Is this a self-serving loophole or a necessary ethic for anyone trying to build something from nothing? Is relying on someone not asking the right question truly a stable ethical position? I wrestle with this question daily.

I started building my startup after I quit my job two months ago. Startups demand ruthless execution, often clashing with strict ethical ideals. I won’t necessarily defend the reckless “move fast and break things” ethos of Silicon Valley. But the reality is, the most effective path isn’t always the most ethical. Those willing to bend the rules often gain an edge. This, at least, hasn’t changed much since the time of Machiavelli.

Machiavelli’s name evokes manipulation, but he wasn’t about evil for its own sake. His primary focus was virtù—effectiveness above all. He was amoral. Critics argue Machiavellian tactics backfire long-term, but this misses the point. True Machiavellianism optimizes for the long game, ethics be damned. By this measure, leaders like Mark Zuckerberg or Sam Altman embody a modern Machiavellian spirit, prioritizing results over ideals.

Even as I find compromises I can live with, a deep unease remains. In this state, I watch the public trajectory of Elon Musk and feel a disturbing tremor of recognition. I see a man who has achieved a level of worldly effectiveness that is almost mythological, the ultimate embodiment of "Win." And yet, he seems trapped in a feedback loop of impulsive actions and chaotic consequences, forever at war with a world he has ostensibly conquered.

Stories are powerful. They are the core meaning-making machinery of any person. From the story of who you are, of who you want to be, of who you were and where you came from, you emerge. Ambitious people tend to over-index on stories of where they want to be, or even deserve to be. But ambition can be dangerous when it totally captures the person—to the point where they are no longer the author of their story, but a character trapped within it.

The narrative of “The Founder,” “The Visionary,” or “The Disruptor” demands constant performance. Every action, every tweet, every conversation becomes a piece of character work. The risk is that after years of performance, there is no one left behind the curtain. The mask becomes the face.

As such, Elon has become a haunted mirror for my own ambition. Looking at him forces me to ask a more terrifying question than the ones Kant or Machiavelli pose. It is not, "Am I good?" or "Am I effective?" It is, "What will be left of me once I have won?" The pursuit of power, I am learning, is a fire that can forge a new world or consume the one who wields it. That, above all, is why I refuse to worship at the altar of absolute effectiveness. The point of this war is not merely to win, but to ensure the person who crosses the finish line is still, recognizably, me.

3. Meaning

“Live to the point of tears.”

- Albert Camus, Notebooks

This fear of becoming a character isn't just an abstract terror I feel when looking at billionaires. It ambushes me in the trenches of the mundane. “There’s nothing quite like endless drudgery,” I thought, after sending my 482nd LinkedIn connection request for my new startup, “to surface existential dread…” I was executing on my cold outreach plan to find customers for my new startup when it hit me: This feels demeaning. What’s the point of this? What’s the point of anything? This startup thing was supposed to be my golden ticket to “meaning.”

The dread that hit me wasn't just about boredom. It was the violent cognitive dissonance between the story I was telling—”I am a Visionary Founder building the future”—and the reality of my actions: I was spending more time sending LinkedIn connection requests and messages than actually building cool shit. Intellectually, of course, I understood that talking to potential users and customers was extremely important, and that building in the dark was a trap, especially in the early stages. But couldn’t shake off the feeling that the cold outreach was somehow beneath me.

Was the grand Visionary Founder story just a lie I'm telling myself to endure? What if the mundane is all there is?

Kant’s grand categorical imperative has nothing to say about the morality of data entry. Machiavelli’s “Win” is useless; there is no opponent here, no tactic, no strategy that can conquer the sheer, soul-crushing volume of the mundane.

My go-to defense was to intellectualize it, to cast myself as a student of Camus rebelling against a meaningless universe. Hell, I even wrote a blog post about it, convinced myself of my own absurd heroism.

But the 483rd connection request calls my bluff. My fingers hover over the keyboard, the cursor a blinking indictment. The "Visionary Founder" in my head is screaming. This isn't building. This isn't creating. This is digital panhandling. The story I tell myself—the myth of the Disruptor—is a universe away from the reality of this text box. The dissonance is a physical weight, pressing my shoulders down.

And then, something shifts. Not a grand epiphany, but a quiet surrender. I give up trying to make the task fit the myth. I stop fighting. I let the "Founder" ego dissolve into the background noise. My focus narrows from the imagined summit of "closing a pilot" to the rocky texture of the immediate ground. Click. Find a name. Type it. Hi [Name]. Copy the template. Paste. Scan their profile for one, just one, authentic detail to add. "Your modernization approach with templates and AI is really interesting." It's not a grand gesture. It's a small act of craft in a sea of repetition. Delete a word. Add another. Hit "Send."

And I prepare for the 484th.

That is the rhythm. It isn’t a beautiful melody; it’s a dull, hypnotic beat. Click. Copy. Personalize. Send. A tiny, perfect loop of action, divorced from outcome. This is the motion that Camus was talking about. It’s not a rebellion of thought, but of muscle memory. In that moment, I am not "The Founder," a noun heavy with the burden of future success. I am simply sending, an anonymous verb. And in this, I find a strange defense against the very loss of self I fear. Victory is not getting a reply. Victory is hitting "Send" and not being destroyed by the pointlessness of it all. Sisyphus is not defined by the peak, because the peak is a fiction. He is defined by the push. By anchoring myself to the verb—building, selling, connecting—I find I cannot be broken by the failure of the noun.

4. Epilogue

I walked home from the Muay Thai gym... drenched in sweat, sore, tired... I had made no progress that day... But there was this strange clarity in the cold. Nothing mattered—not the 484 requests I'd sent, nor the rocket-ship success I dreamed of. Both the drudgery and the destination were cosmically meaningless. All that was real was the cold wind, the tired muscles, and the choice to walk home and do it again tomorrow. It was a burden I had freely chosen. And in that choice, free from the weight of both the mundane and the myth, I felt like myself. It was a brief ceasefire in a lifelong war.

I'm back at my desk.

The empty slide glows. "Our Traction." The cursor blinks. Blink. Blink.

And the ghosts are here again. Not at a dinner table, but standing watch in the dim light of my monitor. Kant, rigid and expectant, a silhouette of pure principle. Machiavelli, a shadow leaning against the doorframe, a glint of victory in his eye. Camus is by the window, a curl of smoke obscuring his face as he looks out at the city lights, profoundly unimpressed.

For years, I waited for their verdict. I sought a unified theory of action that would satisfy the judge, the general, and the jester. But looking at them now, tired to the bone, I see the truth. There is no verdict. There is no unified theory. There is only the blinking cursor. There is only the choice.

Their voices are still there—Is it universal? Will it win? Does it matter?—but they are no longer a firing squad. They are the dissonant chords of a song I am learning to write.

I lean forward. My fingers hover over the keyboard, not with hesitation, but with the deliberateness of a hand placing a stone at the bottom of a hill, ready for the push. I begin typing.

Thanks so much Randall Bennington, Andrew R. Noble, Michael Dean, Evan Hu, Melissa, and Sandra Yvonne! The essay has come a long way from its first shitty draft and your feedback was critical.

This was a fantastic essay, and I read every word. The metaphor of Machiavelli and Kant sitting at a dining table is an excellent and more sophisticated take on the idea of a devil and an angel on your shoulders. It highlights the complex dilemmas I would grapple with if I were to start a business again.

Great writing!!

LOVED pre-prologue part!!